Understanding West Coast Indigenous culture begins at the table

Article content

A Tla-o-qui-aht feast is one part of the naaʔuu experience in Tofino

The crunchy white roe pops in my mouth, salty and tasting of the hemlock where the herring have laid their eggs during their spring spawn.

Herring roe – k’waqmis – is a seasonal treat for the Tla-o- qui-aht people and one Maria Clark is sharing with visitors tonight at naaʔuu, a new Indigenous cultural experience in Tofino.

Clark is the assistant manager of the First Nation-owned Tin Wis Resort where the naaʔuu events are being hosted, and she proffers a branch of roe-encrusted hemlock. The lightly cooked herring caviar is a revelation to me. Herring roe may be an acquired taste, but it’s one that the Indigenous people of Vancouver Island have been enjoying at this time of year for centuries if not millennia.

When the shallow waters turn milky with milt, hemlock boughs are suspended in the sea to capture the masses of

pale, translucent eggs. It’s a sign of the changing seasons, part of the rhythm of living in symbiotic harmony with the coastal environment, which is just one of the Indigenous lessons the naaʔuu experience aims to illustrate with food, stories, music and dance.

A replica longhouse has been constructed inside the Tin Wis Resort’s conference centre for naaʔuu, and we duck through the low doorway to enter, welcomed by a traditional paddle song. It’s dark and smells of freshly sawn cedar, with red floodlights and dry ice replicating the smoky fires of a potlach feast.

“What we want to do with this is to bring people together, to share a meal, and to learn and dialogue,” explains host Tlehpik Hjalmer Wenstob, as he shares the history and traditional origin story of the Tla-o-qui-aht people, one of three local Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations who have lived around Clayoquot Sound more than 10,000 years.

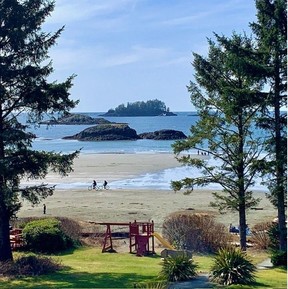

The traditional hahoulthlee (territory) of the Tla-o-qui-aht, Hesquiaht and Ahousaht stretches “all along the mountains”, from the summit at Sutton Pass and Kennedy Lake down to the Pacific Ocean, fertile lands of cedar and salmon, the natural gifts that have long sustained coastal Indigenous people.

Tonight’s early spring menu features these wild seasonal foods, from the herring roe and dried kelp to wild Pacific

salmon, clams, mussels, venison stew with root vegetables, and preserved berries. Like a traditional potlach, it’s a

chance for the hosts to “flex” and show the abundance of nourishing riches from the land and sea.

SHARING HISTORY

As Wenstob stepped up to the podium, his younger brother Timothy Masso is on stage, whirling in the icy fog and seamlessly switching the cedar mask he’s wearing – a smooth face with a blank space where the mouth should be – for another with wide open lips. It’s a new mask that Wenstob carved specifically for this inaugural naaʔuu event, symbolizing the fact that Indigenous people here were once silenced but are now ready to tell their story, in their own way.

“What we’re doing is sharing a history that you may have not heard before,” Wenstob explains. “A lot of the time,

Indigenous histories and our own histories are told from a perspective other than our own, and they can get skewed.”

As we dig into our salmon and shellfish feast, Wenstob narrates the program, explaining the Tla-o-qui-aht spiritual

connection to salmon and cedar, relating millennia of pre-contact history and their creation story, punctuated by

Masso’s masked dances, whether a salmon mask, a mischievous raven or a mask depicting the devastation of

pandemics, from smallpox to COVID.

Wenstob shares stories not often told about the challenges his people have faced since contact, starting with the

American fur trader Capt. Robert Gray, who burned down their village at Opitsaht in the late 18th century, taking with it 200 long houses and as many totem poles, and other colonial confrontations that killed many of their people. A population of 20,000 Tla-oqui-aht people dwindled to less than 2,000.

He also describes how, two centuries later, Nuu-Chah-Nulth fought logging companies and governments to stop clear-cutting in their traditional territory – leading to the famous War in the Woods that eventually saved the towering old-growth forests that now attract visitors from around the globe.

Without divulging any of the sacred songs or stories held by their hereditary chiefs and families, naaʔuu aims to educate non-Indigenous people about the Tla-o-qui-aht connection to this place, seeing the popular tourist destination through an Indigenous lens.

TALL TREES AND WILD FOOD

Another goal of naaʔuu is teaching visitors to respect the natural environment, especially the forest, the ancestral

food garden of the Tla-o-qui-aht people.

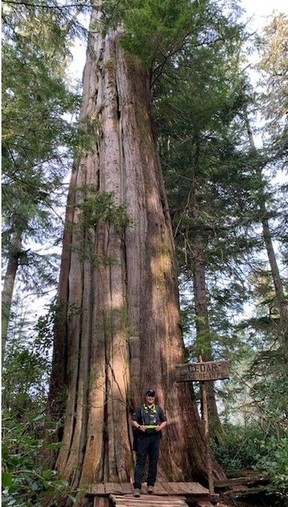

Hiking the Big Tree Trail on Meares Island with Maria Clark and Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks lead Saya Masso, we are

among some of the largest trees still standing in British Columbia. The trail follows along a boardwalk of rough cedar planks built by Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Park Guardians, here where a generation ago others stood to stop clear-cutting of the old-growth forests.

There are spirits here among the ancient trees, and food and medicine, says Clark, scanning the forest floor for young nettles and licorice fern, the root used to soothe a sore throat. It’s traditional knowledge passed through generations.

At the end of the trail, Masso runs his hand along the deep vertical scar of a “culturally modified tree” (CMT) dubbed The Standing Harvest Tree, describing how his people used these trees to survive while letting them survive, too. For millennia, Tla-o-qui-aht used large trees to build long houses, canoes and totem poles, he explains, while carefully harvesting the supple inner bark from standing cedars to use for everything from clothing and hats to woven mats, baskets and rope.

It was the many CMTs standing on Meares Island which proved in Canadian courts that First Nations had been utilizing these forests for centuries, bearing physical witness to their land claims, and leading them to declare this island their first Tribal Park, a designation since extended to the entire Tla-o-qui-aht territory.

Today, Tribal Park Guardians are tasked with stewardship of the Tla-o-qui-aht homelands, their work including

restoration, monitoring, education and enforcement, based on the Nuu-chah-nulth principle of hishukish ts’awalk:

everything is interconnected, everything is one. There are four declared Tribal Parks in Tla-o-qui-aht territory, where visitors are welcomed but expected to “behave with honour dignity, respect and humility.”

COMING TOGETHER AT THE TABLE

Nuu-Chah-Nulth traditional knowledge and teaching is the focus as we gather at their table, whether in the songs and stories about salmon and raven, or the wild mushrooms and berries in the naaʔuu feast.

“This isn’t a potlach, but in Nuu-Chah-Nulth culture, food is a big part of who we are,” says Wenstob, the buffet groaning with locally sourced and prepared dishes. From other local people at our table, we learn how the Nuu-

Chah-Nulth people here are championing language education for their children, the very core of reconciliation and healing.

Elder and former chief Moses Martin is one of the community’s last fluent language speakers, and he describes growing up here in a time of change – from his experiences as a child, fishing with his father, being forced to attend residential school, and then working as a political leader for decades, leading his people in protests to end clear-cut logging and preserve old-growth forests.

Learning to use the proper words in the local Nuu-chah-nulth language, and leaving the anglicized words behind is also important for visitors, he says. It’s a sign of respect – iisaa – which Martin explains is the overarching Nuu-Chah-Nulth law.

“My late father, almost on a daily basis, was talking about the law of respect,” Martin recalls. “What he was saying was that respect is our very first law. If you always base your decisions on the law of respect, no matter what you do or for whatever resource that you’re harvesting, he said there isn’t much that you’re going to do wrong.”

BREAKING BANNOCK – A CULTURAL BRIDGE

Even if you’re ignorant of another culture – and especially if you are – sitting down over a meal is a positive place to start. We are literally breaking bread, the fluffy bannock recipe shared by an elder, to mop up the rich gravy of wild venison stew, as we sip tea infused with the sweet, woody scent of cedar and soak up a new perspective.

When National Indigenous Peoples Day (June 21, formerly National Aboriginal Day) was declared in 1996, a Bannock Awareness recipe book was published, using bannock to represent a bridge between Indigenous and non-indigenous cultures.

“In precontact times, bannock was made from natural substances gathered from the woods: flour from roots, natural leavening agents and a sweet syrup made from the sap of trees,” writes Michael Blackstock in the introduction.

“Unfortunately, most Canadians know little about the history of colonization and its subsequent effects on First Nation’s cultures. We can help build bridges and a brighter future by sharing our favourite recipes and by learning about our history.”

Clark’s gift of her k’waqmis (herring roe) – harvested by local fishermen, and traditionally shared with all community members – feels like a bridge between her culture and mine. She has boiled the boughs to lightly cook the roe, then sprinkled it with sesame oil and smoky kelp seasoning from Naas Foods, an indigenous-led producer of seaweed products in Tofino.

Clark proffers a k’waqmis-covered branch and shows me how to strip away the clumps of tiny eggs and tender

hemlock needles, a wild caviar starter that’s salty and aromatic, a taste of the forest and sea.

The herring spawn just once a year, the roe a seasonal gift of nature and one we’re lucky to enjoy, just as we’re privileged to visit this place – with its tall trees, wide beaches and big surf – and learn how the first people honour their role in it.

The traditional Nuu-Chah-Nulth culture is rooted in gratitude for everything nature provides, a humble understanding that all things are connected, says Wenstob, and without the sacrifice of cedar, whale and salmon the people would never have survived. In his traditional stories, the flora and fauna of the Earth lived in harmony long before humans arrived and “just by being, we threw the balance off.”

Newcomers, he says, brought trade, “but didn’t honour the world around them,” and “seemed to have a desire to consume, take until there’s nothing left.”

It’s brought the planet to a dangerous tipping point, he says. “By following the laws of nature, we can help heal the Earth and return to a place of harmony and balance,” says Wenstob. “The more we can share our stories, the more

connections we have to each other.”

It’s a timely lesson for visitors to take away from the naaʔuu experience.

The Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation in Tofino presented its first naaʔuu event in 2023 with a program designed by carver and gallery owner Tlehpik Hjalmer Wenstob. This year, the event returns with a new artistic director, Ivy Cargill-Martin, a Tla-o-qui-aht multidisciplinary artist, who will add to the experience through her art and storytelling.

Writer Cinda Chavich attended the inaugural naaʔuu event. www.TasteReport.com

IF YOU GO:

THE NAAʔUU FEAST

Naaʔuu events at the Tin Wis Resort run May 24 and 25, and June 7, 8, 14, 15 and 22. Tickets for the three-hour immersive experience ($199-$229 pp) are available through Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and Tribal Parks.

STAY:

Best Western Plus Tin Wis Resort is owned and operated by the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, located on Mackenzie

Beach, just four km from downtown Tofino. The hotel is offering a naaʔuu packaged stay, with discounts on event tickets with a hotel booking. To book, go to the Best Western Tin Wis site, and select your naaʔuu dates for offers.

Tsawaak RV Resort & Campground is for nature lovers who want to stay outdoors or bring their own accommodations. Situated right next to Tin Wis Resort, and also operated by the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation. Phone the resort at 250-266-5015 to book your package directly.

Local tourism allies also have packages for these event dates:

Tofino Resort and Marina is offering 15 per cent off for guests booking their naaʔuu package. Pacific Sands Beach Resort is offering 10 per cent off of the ticket price for guests booking their cultural package.

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.